The devastating winter of 1894 and 1895 dashed the dreams and fortunes of many Florida settlers. Decades would pass before the state fully recovered.

When pioneers began to settle Florida, they found wild oranges among the palm trees. They didn't know they were seeing the ruins of a tragic clash of cultures: the Spanish explorers and Native Floridians.

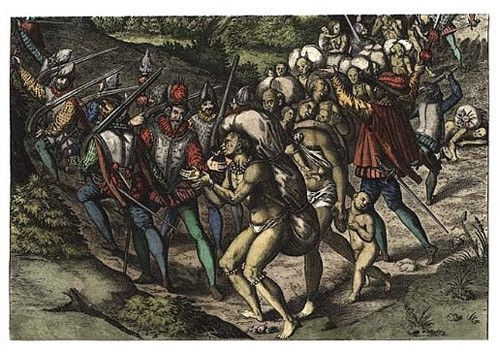

During the 16th century, the Spanish made several ill-fated attempts to settle Florida. Most indigenous people resisted Spanish control and land incursions. But they likely obtained sour orange seeds from the Spanish.

By the 17th century, the Native American population in Florida had completely collapsed. Most succumbed to conflict, slavery, and disease. English settlements pushed the remaining Creeks further south. Later, they joined with former slaves to become the Seminole Tribe.

Over time, Florida settlers bred sweeter oranges more suitable for the mass market. Rural communities saw groves begin to spring up. Farmers started to see the value of orange production. In 1835, a massive freeze hit, killing all the citrus in the Southeast. The temperature was so low that parts of the St. Johns River froze, and people could walk a distance from the shore.

Temperatures bottomed out at seven degrees in Jacksonville. This freeze was worse than the "great freezes" to come. But it actually helped create the Florida orange boom. It ended efforts to grow citrus in Georgia and South Carolina. Pushing more growers south to Florida and warmer weather.

By the 1870s, “Orange Fever” had taken over Florida. The completed railroad allowed farmers to ship citrus across the country. Shipping oranges north became a big business. Farmers and investors flocked to Florida, looking for opportunities.

Henry DeLand, owner of a baking soda empire from New York, purchased a large tract of land in Volusia County. Impressed by the citrus in Orange City, he wanted to build a culture-driven town. This investment would later give birth to the city of DeLand.

Profit from Florida's “Gold” Rush was so sweet that it became the primary industry of the state. Orange growing skyrocketed, and entire towns sprang up around its production.

But on December 29th, 1894, the course of Florida’s history changed forever. Another massive cold front moved through the state. Temperatures logged in Orlando reached an all-time low of 18°F and a frosty 24°F in West Palm Beach. The bitter cold turned the oranges, black on the trees and destroyed most of the crop for the year.

Karl Abbott, whose parents owned the San Juan Hotel in Orlando recalled his boyhood memory of the freeze:

“By 2pm., the San Juan was in an uproar. Prices had dropped to ‘no sale’ commission merchants were frantically trying to get out of options, and heated debates and fistfights started in the lobby. About 9 that night, a fine looking grey-haired man in a black frock coat and Stetson hat walked up the street in front of the hotel and looked at the thermometer, groaned, ‘Oh, my God!’ and shot himself through the head.

For three days icy winds blew over a dead world. The gloom in the San Juan was something you could touch and feel.”

Yet, the worst was still to come. Although the freeze destroyed many young trees, most of the mature trees survived. The next month was warm and wet, which encouraged recovery and new growth. Farmers began to hope, and it was enough incentive for many to dig their heels in and keep trying.

Yet, on February 7th, six weeks after the first freeze, another devastating front hit the state. Temperatures fell to 17 degrees in some places.

Remaining trees, filled with sap from the months of recovery, froze solid. Some recalled the sound of gunshots as whole trees split from trunk to root. In one day, the entire orange industry in Florida was destroyed, crushing the dreams of its unfortunate architects.

After the fall of the orange industry, farmers were unable to pay their debts. Land values plummeted in circus-growing areas and homesteads were abandoned. This allowed wealthy investors free to pick the bones of the Florida market, buying up huge portions of land.

The freezes destroyed more than homesteads. Stores and packing houses closed down, and with them, entire towns vanished. Wildlife was also affected. Turtles and fish died due to the cold weather. Whole colonies of bees starved without orange blossoms.

Before the freezes, Florida produced over six million boxes of fruit a year. After that, the number dropped below 100,000. The freezes damaged the Florida citrus industry so much that it took decades to recover.

Other historic freezes have come and gone since, but their impact has paled in comparison. The great freezes ended eras, fortunes, and communities. Warning Florida farmers to never again bet everything on a single crop.

Sources:

Andrews, Mark. “Devastating Great Freeze Of 1894–95 Put Squeeze On New Citrus Industry.” Orlando Sentinel Website, Orlando Sentinel, December 25th, 1994, http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/1994-12-25/news/9412220310_1_great-freeze-citrus-industry-orange-county

Bowden, Denny. “Florida’s Worst Freezes.” The Florida History Network, 2014, http://www.floridahistorynetwork.com/blog---floridas-worst-freezes.html

Clark, J. C. (2013). Orlando, Florida: a brief history. Charleston, SC: The History Press.

Comments